Using a Light Touch

Analyzing Delicate Macromolecules with MALDI

Analyzing Delicate Macromolecules with MALDI

“Please call me Mister. I’m not a Doctor, I’m an engineer,” requested a very modest Koichi Tanaka at a 2003 reception held in his honor at the Maryland Science Center in Inner Harbor, Baltimore. Graduating from the School of Engineering at Tohoku University with a Bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering in March of 1983, Tanaka accepted a position in the nascent Central Research Laboratory of the Shimadzu Corporation in April of that year. Along with a fellow new graduate and three experienced researchers, their five-member project team was tasked with exploring the utility of advanced laser technology in analytical instrumentation. Their work centered on the development of a laser-ionization microprobe mass spectrometer. Although no member of the team had received formal training in organic chemistry, Tanaka accepted the task of sample preparation and familiarized himself with solvents and solution chemistry.

Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

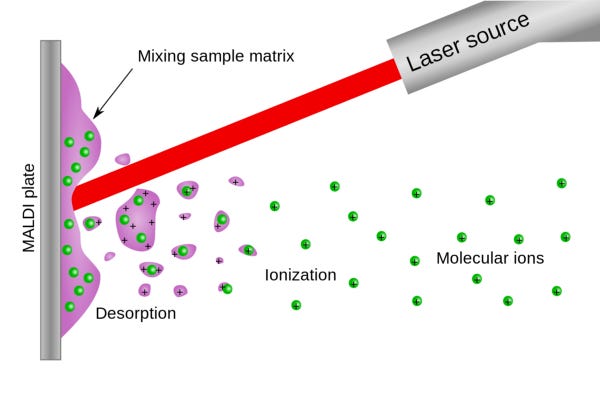

Designed to serve as a photonic alternative to electron ionization (EI) and fast atom bombardment (FAB), the team’s initial instrument used a laser to vaporize a solid sample that was subsequently analyzed by a time-of-flight (TOF) spectrometer. The instrument performed well but displayed little competitive advantage over the traditional ionization methods. During its development, team member Yoshikazu Yoshida had discovered a method for “softening” the laser intensity felt by the sample by mixing it into a supporting solid matrix of ultra-fine cobalt powder, thereby permitting the analysis of higher molecular weight samples. While considering whether the laser project deserved further investigation, a Shimadzu scientist involved with the development of instruments targeted for the pharmaceutical- and chemical-manufacturing industries suggested the “soft” ionization provided by the laser might show promise for the ionization of large biological macromolecules that were routinely destroyed by the traditional “hard” ionization methods. Armed with a more specific mission statement, the project team set to the task of producing a laser ionization method capable of generating intact macromolecular ions from biological samples.

Initially, it appeared the laser ionization technique thermally decomposed the biological macromolecules into small unusable fragments. Tanaka was charged with optimizing Yoshida’s soft-ionization cobalt matrix sample preparation method while the other members set to the tasks of optimizing the components of the TOF instrument for the analysis of a target mass of 10,000 Daltons. He systematically adjusted the concentration and preparation procedure of the cobalt matrix, but did not observe an appreciable effect. During the preparation of one of the many trials, Tanaka mistakenly dissolved the cobalt into an aliquot of glycerin rather than the acetone that was normally used for its rapid evaporation from the sample under vacuum. He discovered his mistake quickly thanks to the obvious differences in viscosity but, rather than discard the sample, he noted it and included it with the other samples for analysis. Unexpectedly, the high mass peak of the sample’s molecular ion showed up on the mass spectrum. The team quickly verified the result with additional runs, and soon optimized the sample preparation and analysis parameters such that their TOF instrument could analyze molecules of up to 35,000 Daltons; shattering their target by more than a factor of three.

Tanaka and team-leader Tamio Yoshida jointly filed for a patent for the glycerin-cobalt laser ionization method in August of 1985 and the team quietly worked on the development of a commercial instrument. Two years later, Tanaka presented a poster at the 2nd Japan-China Joint Symposium on Mass Spectrometry, where leading researchers lamented the inability of laser-ionization techniques to analyze large molecules, and shared his most recent analysis of macromolecules having a mass number of up to 72,000 Daltons. His results swept the symposium by storm and a paper in English quickly appeared in Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry in 1988. Soon afterward, the mass spectrometry community coined the method “Matrix-assisted laser-desorption ionization” (MALDI).

Today, commercial MALDI-TOF instruments provide a very rapid method for the identification of proteins and amino-acid sequences and have facilitated the explosion in proteomics research. For his contribution, Koichi Tanaka shared in the 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, a fact that he finds highly improbable given his terminal undergraduate degree in engineering. Regardless of whether his discovery was made during his career in industry or as a graduate student, a precious few people can wield the title “Nobel Laureate.”

This material originally appeared as a Contributed Editorial in Scientific Computing and Instrumentation 20:09 August 2003, pg. 13.

William L. Weaver is an Associate Professor in the Department of Integrated Science, Business, and Technology at La Salle University in Philadelphia, PA USA. He holds a B.S. Degree with Double Majors in Chemistry and Physics and earned his Ph.D. in Analytical Chemistry with expertise in Ultrafast LASER Spectroscopy. He teaches, writes, and speaks on the application of Systems Thinking to the development of New Products and Innovation.