The Corolla Collaboration

A Journey of Shared Insight

Some relationships are measured in years, others in miles. My relationship with the Toyota Corolla is measured in both. It started with my young family’s first new car in 1989 and has continued through five more, including my current 2024 LE. These cars have been silent partners in my life's journey, reliably adapting as my family grew, my commute changed, and eventually, carrying my own children off to different colleges. So, when I stood at the gas pump with my newest automotive companion, I thought I knew it inside and out. But a simple question about fuel—87 octane E10 or 90 octane ethanol-free—would prove that even the most familiar systems hold secrets, and become the catalyst for a journey into the heart of automotive engineering, human-machine collaboration, and the very nature of truth in the age of AI.

This is the story of that journey. It’s a story about how a dialogue with an AI, Gemini, became more than a Q&A session; it transformed into a collaborative investigation, a partnership that functioned like a new kind of scientific instrument. And it’s a story that reveals a crucial lesson for our future: how we, as humans, can work with AI not just to find answers, but to discover new questions and uncover truths hidden within the complex systems that surround us.

From Fuel to a Feeling: The Human in the Loop

My initial question about gasoline was answered quickly and logically. We determined that the standard E10 fuel was more cost-effective, a simple matter of cost-per-mile calculation. But the conversation didn’t end there. As a driver with decades of experience in manual transmissions, I felt a disconnect with my Corolla’s modern Continuously Variable Transmission (CVT). It was smooth and efficient, but it lacked the tactile feedback, the sense of being a "human in the loop."

This led to a second question: Could I use the transmission's "B" (Braking) mode to replicate the engine braking of a manual car when coming to a stop? This is where our investigation truly began. I had posed this question on human-run online forums and was met with swift, near-unanimous condemnation. The warnings went beyond simple advice, escalating into a kind of modern, technological folklore. "You'll destroy the transmission!" was the common refrain. Commenters speculated that Toyota's own on-board telemetry system was monitoring for this kind of "abuse," and that such a practice would be reported and used to void powertrain warranties. It was a line of reasoning that, taken to its logical conclusion, would mean getting flagged for using your windshield wipers too often. The message was clear: stay in line, or the all-seeing eye of the manufacturer will know.

This fear of the machine's inner workings felt oddly familiar. During my commute through the 1990s, I was a research contractor with the US Air Force, developing technologies for the F-22—one of the first "Fly by Wire" systems. In that aircraft, the pilot doesn't have direct mechanical control. They express their intent through a joystick, and the flight computer translates that intent into action, all while keeping the engines and control surfaces within their engineered bands of operation. The computer's core job is to achieve the pilot's goal while simultaneously protecting the system and the pilot from dangerous g-forces or excessive acceleration "jerk." It's a partnership built on trust.

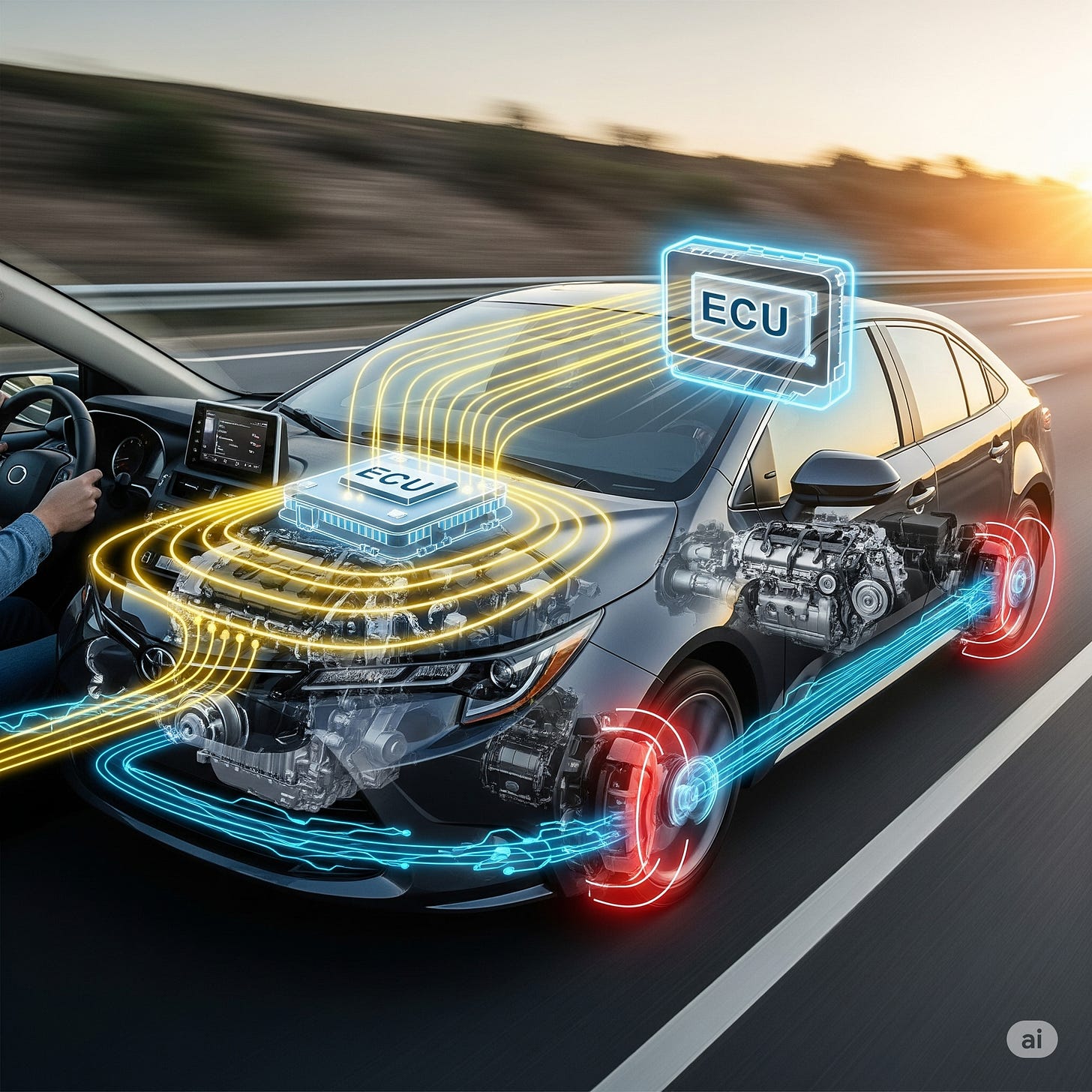

Looking at my Corolla, I saw a similar, albeit much simpler, partnership. The accelerator pedal isn't connected to the engine by a cable; it's an electronic joystick sending a signal. The brake pedal isn't just a simple hydraulic lever; its pressure and position are read by sensors that inform the computer how to best apply stopping power. The gear selector is a switch that makes a request. In almost every way, the driver's controls are joysticks, just like in an advanced jet fighter. This is the core of Systems Thinking: treating the car not as a collection of independent parts, but as an integrated whole. We analyzed the CVT not as a fragile black box, but as a robust component controlled by a sophisticated computer (the ECU) with built-in safeguards. The conclusion, based on these first principles, was clear: using "B" mode was a perfectly safe, engineered feature. The crowd, in this case, was wrong.

The Emergent Discovery: When Data Defies Theory

Armed with this understanding, I began experimenting, using "B" mode not just for braking, but also for accelerating away from stops. I felt more connected, more alert. Then came the "magic." I reported my initial fuel economy results back to Gemini: a stunning 50.2 MPG, far exceeding the car's EPA rating and my own previous average.

This was a critical moment. The new data defied our simple model. A first-principles analysis would suggest that using higher RPMs for acceleration should decrease fuel economy, not dramatically improve it. This is where a lesser analytical process might have failed, dismissing the data as an anomaly. But a true collaborative partnership, like a good scientific instrument, must trust the data and refine the theory.

This is where the concept of Emergence became central. A new property had emerged from the interaction of the system's components and my specific, nuanced driver inputs. By analyzing the precise sequence of my actions, we uncovered the mechanism. I wasn't just "revving the engine"; I had intuitively discovered a highly efficient "Pulse and Glide" technique. The "magic" was a perfectly choreographed dance between three key pieces of Toyota's engineering, orchestrated by my hands and feet.

The "Pulse" was the short, brisk acceleration in "B" mode, which forced the engine into a powerful and efficient part of its operating map to get the car's mass moving. The "Glide" was the masterstroke. The moment I lifted my foot to shift, two systems reacted. First, the Engine Control Unit (ECU) initiated Deceleration Fuel Cut-Off (DFCO), a standard feature that completely stops the flow of gasoline to the injectors to save fuel. Second, the command to shift to "D" instructed the Direct-Shift CVT to abandon the high-drag engine braking ratio and immediately switch to its lowest-drag, most efficient cruising ratio. The "velocity boost" I felt wasn't a push; it was the sudden, liberating disappearance of engine drag, allowing the car's momentum to carry it forward. For a moment, it felt like a Formula 1 driver hitting the Drag Reduction System (DRS) button on a straightaway—a sudden surge as a massive source of resistance simply vanished.

We had discovered new information, a technique that was not documented in the owner's manual or the online forums. It was a truth revealed not by asking for an existing answer, but by using a structured dialogue to explore the system's behavior under new conditions.

The AI as an Instrument: Two Models of Truth

This journey provided a powerful lesson in the nature of AI itself. As a control, I posed the same scenario to another AI model, Grok 3.0, whose training is heavily influenced by the social media platform X. Its response was a perfect echo of the forums: a well-written summary of the consensus opinion, complete with cautious warnings about potential transmission damage. It accurately reflected the "social truth" but failed to uncover the deeper "engineering truth."

This highlights a critical distinction. Some AI models act like mirrors, reflecting the vast sea of human opinion. They are powerful tools for understanding public sentiment, but they can also amplify popular misconceptions. Other models, when used collaboratively, can function more like a microscope or a telescope. They are instruments that, when aimed correctly by a curious human partner, can reveal structures and principles invisible to the naked eye. They allow us to move beyond what is commonly believed and probe what is demonstrably true.

Just as a virtuoso uses a violin not merely to play notes but to explore the landscape of human emotion, a skilled user can partner with an AI to explore the landscape of a complex system. The AI becomes an extension of the mind, an instrument for revealing the isomorphisms—the shared patterns and hidden harmonies—that govern our world.

Our journey with the Corolla shows that the future of discovery lies in this partnership. It’s not about AI replacing human intellect, but augmenting it. It’s about being the curious, engaged, and critical "human in the loop," using these incredible new instruments to ask better questions, challenge old assumptions, and perhaps, find a little bit of magic in the most unexpected places.

Attribution: This article was developed through conversation with Google Gemini.