The Consequence Gap in AI

Moving Beyond the Next Token

In the rush to integrate—or ban—Artificial Intelligence in higher education, we often get bogged down in the mechanics of the tool. We argue about plagiarism, we worry about “hallucinations,” and we marvel at the speed of the output. But as we navigate this new “River of Reality,” we need a simpler compass to distinguish the machine from the mind.

After thirty years of working with the algorithms that underpin these systems, I propose a fundamental dividing line. It is a distinction that clarifies not just what AI is, but what our job as educators must become.

AI predicts the next word. Humans predict the consequence.

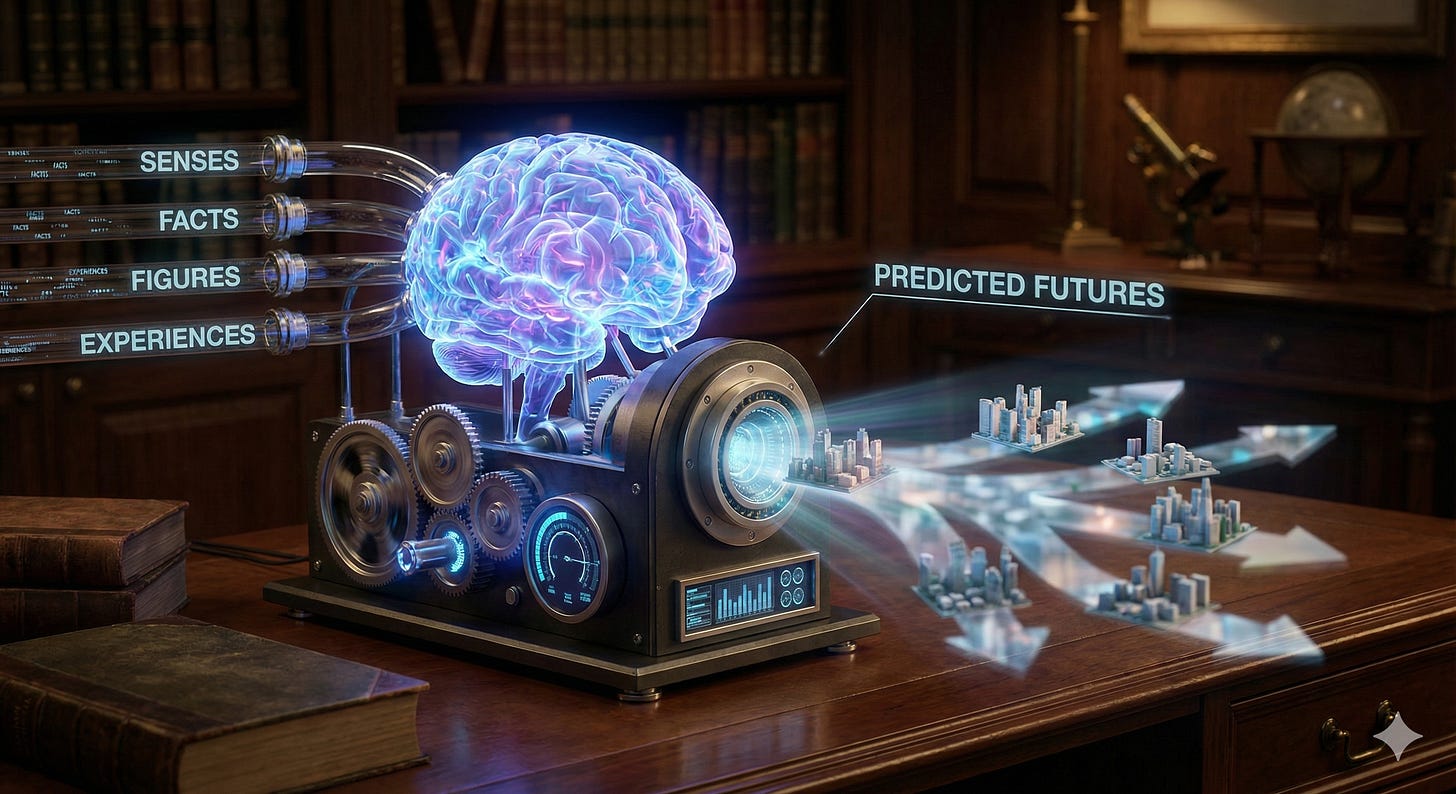

The Prediction Machine

To understand this divide, we must look back to Jeff Hawkins’ seminal 2005 work, On Intelligence. Long before the transformer models of today, Hawkins argued that the human neocortex is fundamentally a biological machine designed for prediction. It builds a model of the world, constantly projecting what it expects to see, hear, and feel. When our sensory reality clashes with that prediction, our brain adjusts its model to minimize the error. That process of correction is what we call “thinking.”

This definition gives us the perfect lens to view our current situation. Both the AI and the human are prediction engines, but they are predicting entirely different timelines.

The Autocomplete Engine

At its core, a Large Language Model (LLM) is minimizing a very specific, shallow type of error. It is a master of syntax, trained on the vast corpus of human text to determine which word is statistically most likely to follow the one preceding it. It looks backward at its training data to construct a forward path of text.

However, the “reality” it checks against is merely the statistical likelihood of a token. It does not compare its prediction against the physical world or social reality. To the AI, the “right” answer is simply the most probable one. It has no neocortex to simulate the pain of a cruel remark or the failure of a bridge design; it only simulates the grammar of the sentence describing them.

The Human Independent Variable

Humans, conversely, have advanced biologically to predict beyond the immediate sensory input. We consider the consequences of uttering the words. We run complex simulations in our “wetware” that extend far into the future.

If I say this to my colleague, how will it affect our working relationship?

If I implement this circuit design, what happens when the temperature drops to -40 degrees?

If I publish this finding, who might misuse it?

This is the evolution of Hawkins’ concept. We are not just predicting the next photon to hit our retina; we are predicting the second and third-order effects of our actions. This is “Humanics,” as Joseph Aoun might frame it in Robot Proof. It is the ability to see beyond the immediate output to the systemic ripple effects.

The Ethics of Output

This distinction echoes a cultural wisdom that transcends religious dogma. In the teachings of Jesus Christ, we find the instruction that it is not what goes into the mouth that defines a person, but what comes out of it.

While originally a lesson on spiritual purity versus legalistic ritual, it serves here as a powerful metaphor for modern intelligence. An AI is a machine of inputs; it “ingests” data and follows strict syntactic “dietary laws” to generate clean, grammatical text. It is technically pure, adhering to the strict rule set of its training. But it is utterly indifferent to the compassion or cruelty of its output.

Humans, however, are burdened with the knowledge that what comes out of our mouths—or our keyboards—has the power to wound or to heal. We understand that adhering to the rules of grammar is secondary to the rule of consequence. To focus only on the mechanics of the input is to miss the weight of the result.

Teaching the Divide

If we accept this distinction, our pedagogical strategy shifts. We stop asking students to merely produce words (which the AI can do faster) and start asking them to evaluate consequences (which the AI cannot do at all).

This alignment effectively bifurcates Bloom’s Taxonomy. The AI dominates the lower levels: Knowledge and Comprehension. It is the ultimate engine for recalling facts and organizing information with statistical precision. However, the human mind must occupy the higher-order levels of Evaluation and Synthesis. While an AI can synthesize text based on probability, only a human can synthesize a solution based on consequence. We must teach students to use the AI as a foundation—a distinct lower-level tool—upon which they build their higher-order judgments.

We must design “wicked problems” where the correct answer depends entirely on the context and the fallout. We can let the AI generate the plan, but we must grade the student on their ability to predict where that plan will fail, whom it will hurt, and why it might be technically accurate but morally disastrous.

One powerful instructional method is to treat the AI as a probability partner rather than an oracle. In this model, students propose hypothetical outcomes derived from an AI-generated solution. They then feed these outcomes back into the system, asking the AI to rate them based on probability and rank them statistically.

Here, the critical thinking engages. The student must audit this ranking: Does the AI’s statistical probability align with human reality? They provide feedback to the AI, challenging its weights based on ethical or physical constraints. Finally, they can push the simulation further, asking the AI to extrapolate those top-ranked outcomes five or ten years into the future. This iterative loop forces the student to be the pilot, using the AI’s predictive power to map the river, while reserving the decision of which channel to navigate for themselves.

In the River of Reality, the AI is the current—powerful, relentless, and directional. But the human is the navigator, the only one capable of seeing the waterfall ahead.

Attribution: This article was developed through conversation with Google Gemini 3.0

The "Sheldon Cooper" Problem: A Cultural Analogy for AI

If you are struggling to explain the difference between Generative AI and Human Intelligence to your students (or colleagues), look no further than our favorite sci-fi icons of "Logical Excellence."

The AI is Mr. Spock, Data, and Sheldon Cooper.

Like an LLM, these characters possess massive data retrieval capabilities and perfect syntactic logic. They can calculate the trajectory of a starship or the physics of a black hole in seconds. However, they are famous for being "comedically offensive while true."

Sheldon states a fact that ruins the dinner party.

Data pushes a button that saves the ship but inadvertently insults the Admiral.

They predict the next logical token, but fail to predict the social consequence.

The Human is Kirk, Picard, and Penny.

These characters serve as the "Humanics" layer—the top-level prediction engine.

Penny explains to Sheldon why his technically correct statement is socially disastrous.

Picard weighs Data’s probability calculation against the ethical cost of the Prime Directive.

Kirk takes Spock’s odds of survival (3,720 to 1) and decides to take the risk anyway because he understands the human spirit.

The Lesson:

We are not training our students to be the computer. We are training them to be the Captain. We need them to take the "Sheldon" output of the AI and apply the "Penny" filter of consequence, empathy, and context.

Discussion Question: How do you teach your students to be the "Captain" of their AI tools?