Attitude Adjustment

A Look at Mechanical and Optical Gyroscopes

A Look at Mechanical and Optical Gyroscopes

Early on a Saturday afternoon this past June, physicist Carl Walz heard a mysterious growling noise that grew louder as time passed. He radioed Mission Control to inform them that the noise was emanating from an 800-pound control moment gyroscope (CMG) spinning at 6500 rpm, one of four aboard the International Space Station (ISS). Telemetry revealed faulty lubrication caused a bearing to overheat and seize. Gyroscopes are useful for detection of rotational motion. In machines such as air- and spacecraft, measurement of orthogonal motions of roll, pitch, and yaw; corresponding to rotation about the x, y, and z axes respectively, is paramount in keeping the craft on course and from tumbling out of control.

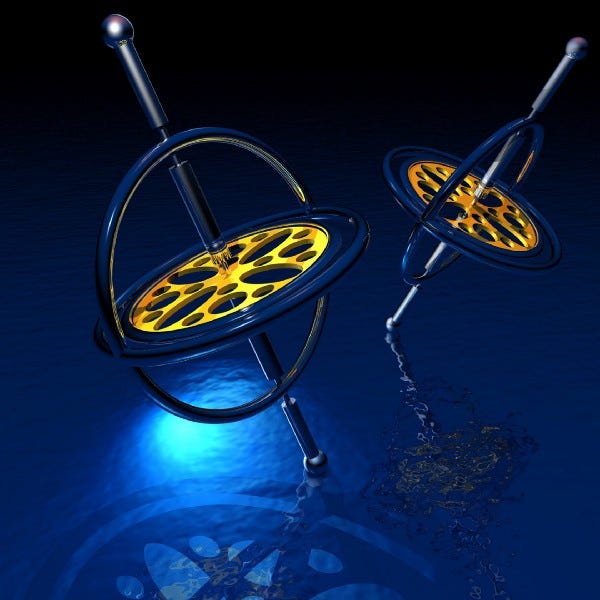

Photo by Stevebidmead on Pixabay

Gyroscopic action, such as that exhibited by a spinning top, can at first seem counter-intuitive as the resultant direction of motion is modeled by the cross product between an applied force and angular momentum vectors. The downward gravitational force on a spinning top results in precession about the vertical axis. If the spinning top is held stationary by low-friction bearings at both ends by what is known as a gimbal mount, an appreciable force is required to change the direction of the top’s angular momentum in the same way that a large amount of force is required to change the linear momentum of a locomotive. When supported by a set of three gimbals permitting unfettered xyz rotation, the spinning top continues to spin in its original direction while the gimbal housing is rotated in all directions. Placement of rotary angle encoders on the gimbal joints permits the three-axis rotation of the housing relative to the spinning top to be determined.

The massive CMGs aboard ISS have motors on the gimbal joints used to change the angular velocity of the spinning mass. Reactionary forces produced by this change gently rotate the 150-ton station into the desired attitude, obviating the use of propellant-fired stabilization thrusters. When used only as a rotation indicator, the rotating mass can he miniaturized to fit an airplane cockpit or ship’s bridge.

An effort to reduce the mechanical gyroscope’s complexity and inherent friction spurred development of the optical gyroscope (OG). The OG replaces the spinning mass with a pair of counter-rotating laser wavefronts contained in a ring cavity. Typically triangular rather than circular, the laser gain medium resides in one of the triangle’s legs, and cavity mirrors are placed at the vertices. Whereas a typical ring laser employs a Faraday isolator to select one of the wavefront directions, the OG permits both clockwise (cw) and counterclockwise (ccw) wavefronts to oscillate in the ring cavity. A detector monitors the interference pattern created by interaction of both wavefronts. When the optical cavity is rotated, the wavefront traveling with the rotation encounters a longer pathlength, while the opposite wavefront traverses a shorter distance. The resulting subtle change in detected interference pattern can be calibrated for rotation angle.

Increased sensitivity and resolution can be gained by increasing the path-length of the ring laser cavity. Without sacrificing practicality, the optical ring cavity can be increased to hundreds of meters using single-mode optical fiber. The typical fiber optic gyroscope (FOG) employs a single semiconductor laser whose output is modulated and split into cw and ccw propagation directions along a circular loop of fiber optic. Nested loops can be mounted in orthogonal directions to detect rotation along all three cardinal axes.

The vibrating gyroscope (VG) represents a third class of devices created to measure rotation. A miniature piezoelectric crystal having the form of a two-tine tuning fork or a multi-tine comb is driven at its resonate frequency. During rotation, the tines are deflected out of the resonate plane, similar to the action of a centrifugal clutch, generating oscillation harmonics that are detected and calibrated for rotation angle. The VG can he miniaturized using MEMS technology and has found popular application in robotics. When combined with MEMS accelerometers, a complete inertial navigation system on a single chip could be manufactured and incorporated into PDAs and cell phones. Perhaps then we will be able to answer the question, “It’s 10 o’clock. Do you know where your children are?”

This material originally appeared as a Contributed Editorial in Scientific Computing and Instrumentation 19:12 November 2002, pg. 15.

William L. Weaver is an Associate Professor in the Department of Integrated Science, Business, and Technology at La Salle University in Philadelphia, PA USA. He holds a B.S. Degree with Double Majors in Chemistry and Physics and earned his Ph.D. in Analytical Chemistry with expertise in Ultrafast LASER Spectroscopy. He teaches, writes, and speaks on the application of Systems Thinking to the development of New Products and Innovation.